|

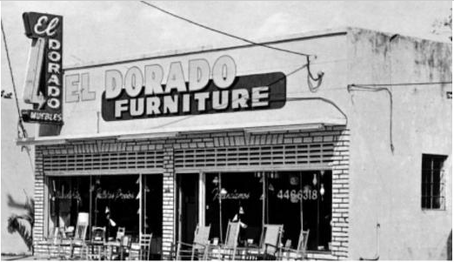

Little Havana became the social, economic and political center for Cuban exiles. By the early 1970’s, thousands of Cuban small businesses lined Calle Ocho (See Figure 1). The Cuban population density in Little Havana increased as the influx of immigrants motivated by economic factors continued to rise. By 1970’s, over 85 percent of the area’s population was Cuban. Despite the increase of Little Havana’s cultural significance, it remained as a low-income residential district providing cheap housing to new immigrants. On the other hand, Cubans who are economically stable started moving to the suburbs.

Local political leaders saw a potential development opportunity in Little Havana. Over $8 million was designated to redevelop the area. In 1978, the city’s planning department hired Jose Casanova, a Cuban-born architect, to lead the development projects in Little Havana. The redevelopment of Little Havana continued to grow as they hold festivals and beauty pageants. Cigar companies also contributed in Little Havana’s economic success. |

Figure 2: Jose Marti Park, 2008

Figure 2: Jose Marti Park, 2008

However as political heat increased, population aged, and influx of the immigration of Cuba’s unskilled workers heightened, the deterioration of the neighborhood was being more apparent. According to a 1986 study of residents in Little Havana by Florida International University, about two-thirds of the population over sixty earned less than $7,000 annually. In 1980’s, with low rents and high crime rates, the neighborhood continued to decline. City leaders felt the need to take over, and they did so by creating a task force that would aimed to revive twenty-one blocks of East Little Havana and control the damage to the rest of Little Havana.

The influx of Cuban immigrants affected Miami’s minority communities. For African Americans, Mariel boatlift immigrants meant more job competition. The economic success of Cuban immigrants also magnified African Americans’ marginalization. This contributed to the friction between Cuban and African Americans.

In 1984, the Miami City Commission approved a plan to turn sixty square blocks of Little Havana into a tourist destination: Latin Quarter. The Quarter was divided in to three separate zoning districts. Each district had residential and commercial uses. The Quarter aimed to preserve Little Havana that is the central hub of exile community in Miami. The establishment of Latin Quarter divided Little Havana into two groups: supporters and resistors. This plan resulted in the construction of better sidewalks, painting facades, repavement of the streets, building of the Latin Quarter Specialty Center, and construction of Jose Marti Park (See Figure 2). [1]

The influx of Cuban immigrants affected Miami’s minority communities. For African Americans, Mariel boatlift immigrants meant more job competition. The economic success of Cuban immigrants also magnified African Americans’ marginalization. This contributed to the friction between Cuban and African Americans.

In 1984, the Miami City Commission approved a plan to turn sixty square blocks of Little Havana into a tourist destination: Latin Quarter. The Quarter was divided in to three separate zoning districts. Each district had residential and commercial uses. The Quarter aimed to preserve Little Havana that is the central hub of exile community in Miami. The establishment of Latin Quarter divided Little Havana into two groups: supporters and resistors. This plan resulted in the construction of better sidewalks, painting facades, repavement of the streets, building of the Latin Quarter Specialty Center, and construction of Jose Marti Park (See Figure 2). [1]

Sources:

[1] Grenier, G. J., & Moebius, C. J. (2015). A History of Little Havana. Charlston, SC: The History Press.

Images:

Figure 1: Grenier, G. J., & Moebius, C. J. (2015). A History of Little Havana. Charlston, SC: The History Press.

Figure 2: Grenier, G. J., & Moebius, C. J. (2015). A History of Little Havana. Charlston, SC: The History Press.

[1] Grenier, G. J., & Moebius, C. J. (2015). A History of Little Havana. Charlston, SC: The History Press.

Images:

Figure 1: Grenier, G. J., & Moebius, C. J. (2015). A History of Little Havana. Charlston, SC: The History Press.

Figure 2: Grenier, G. J., & Moebius, C. J. (2015). A History of Little Havana. Charlston, SC: The History Press.