Great Miami Hurricane of 1926The Great Miami Hurricane is still one of Florida’s most destructive storms. It hit the coastal city in September 18, 1926 causing its economic boom to crash. It was one of the fastest growing cities in 1925. The economic growth the city faced was so fast that there were shortages of materials for the construction of new homes. Many new settlers had to live in camps made of tar paper tents in suburbs in Miami. By spring of 1926, the real estate market dropped and then in September, the hurricane hit causing the economic success to come to an end and causing the city to go into a depression. [1]

This storm destroyed about five thousand homes and damaged about nine thousand houses causing at least twenty-five thousand people to become homeless in Miami. The windows and roofs of almost all the buildings, residential or not, were practically blown out due to the high velocity of wind from the storm. [2] The cause of so much damage was from the poor building codes that were in place during that time:

|

Hurricane Andrew

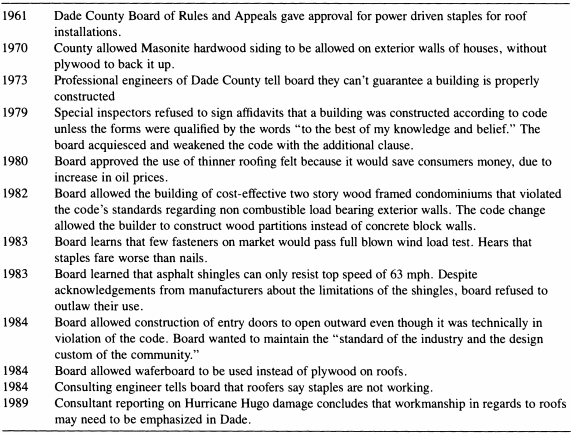

Figure 3: Changes in build codes from 1961-1989

Figure 3: Changes in build codes from 1961-1989

Hurricane Andrew hit Southern Miami-Dade County on August 24, 1992. It was the third strongest hurricane to hit the United States in the 20th century. The hurricane destroyed/damaged 126,000 single family houses and destroyed 9,000 mobile homes. City officials ordered the bulldozing of destroyed homes because nothing was salvageable and on those sites, temporary housing was put up. [5]

Through analyzing the destruction the storm caused, older houses, those built before the 1960s, seemed to have less damage than newer houses. The low quality of construction, design, and materials were found to be things that the newer houses had in common, this played a role in how much damage the houses took. Although the South Florida Building Code in 1957 was considered to be the strongest code in the nation, building standards decreased over the years so houses could be built more quickly. One example is the approval of having power driven staples for roof construction instead of having roofers hand nail roofs on. The figure about shows how the build code was weaken from 1961-1989, thus allowing builders to have lower quality materials. [6]

However, the city is not responsible for all the blame in lower quality homes. Consumers and modernization are also to blame. Cheaper material for homes meant lower build cost and thus lower priced homes for those living in Florida. Modernization caused wood-framed houses to suffer more damage than those made of concrete and block. [6]

After the hurricane, build code requirements were updated and enforced to better stand against hurricanes. One of the first standard Florida embraced was ASCE-7 code by the American Society of Civil Engineers. This code says the building has to meet a requirement for general structure design. An addition to the code that is essential to Miami and all other hurricane prone cities and states was the requirement of missile-impact resisting glass that can withstand high velocity impact because of high velocity winds that occur during hurricanes. Another code that was changed was the building of wood-framed houses. Most of the homes are now built with cinderblock reinforced with concrete pillars, hurricane-strapped roof tresses, and along with other requirements for roofing and adhesives. [7]

Through analyzing the destruction the storm caused, older houses, those built before the 1960s, seemed to have less damage than newer houses. The low quality of construction, design, and materials were found to be things that the newer houses had in common, this played a role in how much damage the houses took. Although the South Florida Building Code in 1957 was considered to be the strongest code in the nation, building standards decreased over the years so houses could be built more quickly. One example is the approval of having power driven staples for roof construction instead of having roofers hand nail roofs on. The figure about shows how the build code was weaken from 1961-1989, thus allowing builders to have lower quality materials. [6]

However, the city is not responsible for all the blame in lower quality homes. Consumers and modernization are also to blame. Cheaper material for homes meant lower build cost and thus lower priced homes for those living in Florida. Modernization caused wood-framed houses to suffer more damage than those made of concrete and block. [6]

After the hurricane, build code requirements were updated and enforced to better stand against hurricanes. One of the first standard Florida embraced was ASCE-7 code by the American Society of Civil Engineers. This code says the building has to meet a requirement for general structure design. An addition to the code that is essential to Miami and all other hurricane prone cities and states was the requirement of missile-impact resisting glass that can withstand high velocity impact because of high velocity winds that occur during hurricanes. Another code that was changed was the building of wood-framed houses. Most of the homes are now built with cinderblock reinforced with concrete pillars, hurricane-strapped roof tresses, and along with other requirements for roofing and adhesives. [7]

Sources:

[1] Barnes, J. (2007). Florida’s Hurricane History. North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press.

[2] Newton-Matza, M. (2014). Disasters and Tragic Events: An Encyclopedia of Catastrophes in American History. Santa Barbra, CA. ABC-CLIO, LLC.

[3] FEMA. (2005). Coastal Construction Manual, Volume I: Principles and Practices of Planning, Siting, Designing, Constructing, and Maintaining Buildings in Costal Areas.

[4] Neely, W. (2009). The Great Bahamian Hurricanes of 1926. Bloomington, IN. iUniverse.

[5] U.S Department of Commerence (1992). National Disaster Survey Report: Hurricane Andrew: South Florida and Louisiana August 23-26, 1992. Retrieved from http://www.nws.noaa.gov/om/assessments/pdfs/andrew.pdf

[6] Frostin, P & Holtmann G. A. (1994). The Determinants of Residential Property Damage Caused by Hurricane Andrew. Southern Economic Journal, Vol. 61, No. 2. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/1059986?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

[7] Tsikoudakis, M. (2012, Aug 19). Hurricane Andrew Prompted Better Building Code Requirement. Business Insider. Retrieved from http://www.businessinsurance.com/article/20120819/NEWS06/308199985

Images:

Figure 1:Newton-Matza, M. (2014). Disasters and Tragic Events: An Encyclopedia of Catastrophes in American History. Santa Barbra, CA. ABC-CLIO, LLC.

Figure 2: FEMA. (2005). Coastal Construction Manual, Volume I: Principles and Practices of Planning, Siting, Designing, Constructing, and Maintaining Buildings in Coastal Areas.

Figure 3: Frostin, P & Holtmann G. A. (1994). The Determinants of Residential Property Damage Caused by Hurricane Andrew. Southern Economic Journal, Vol. 61, No. 2. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/1059986?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

[1] Barnes, J. (2007). Florida’s Hurricane History. North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press.

[2] Newton-Matza, M. (2014). Disasters and Tragic Events: An Encyclopedia of Catastrophes in American History. Santa Barbra, CA. ABC-CLIO, LLC.

[3] FEMA. (2005). Coastal Construction Manual, Volume I: Principles and Practices of Planning, Siting, Designing, Constructing, and Maintaining Buildings in Costal Areas.

[4] Neely, W. (2009). The Great Bahamian Hurricanes of 1926. Bloomington, IN. iUniverse.

[5] U.S Department of Commerence (1992). National Disaster Survey Report: Hurricane Andrew: South Florida and Louisiana August 23-26, 1992. Retrieved from http://www.nws.noaa.gov/om/assessments/pdfs/andrew.pdf

[6] Frostin, P & Holtmann G. A. (1994). The Determinants of Residential Property Damage Caused by Hurricane Andrew. Southern Economic Journal, Vol. 61, No. 2. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/1059986?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

[7] Tsikoudakis, M. (2012, Aug 19). Hurricane Andrew Prompted Better Building Code Requirement. Business Insider. Retrieved from http://www.businessinsurance.com/article/20120819/NEWS06/308199985

Images:

Figure 1:Newton-Matza, M. (2014). Disasters and Tragic Events: An Encyclopedia of Catastrophes in American History. Santa Barbra, CA. ABC-CLIO, LLC.

Figure 2: FEMA. (2005). Coastal Construction Manual, Volume I: Principles and Practices of Planning, Siting, Designing, Constructing, and Maintaining Buildings in Coastal Areas.

Figure 3: Frostin, P & Holtmann G. A. (1994). The Determinants of Residential Property Damage Caused by Hurricane Andrew. Southern Economic Journal, Vol. 61, No. 2. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/1059986?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents